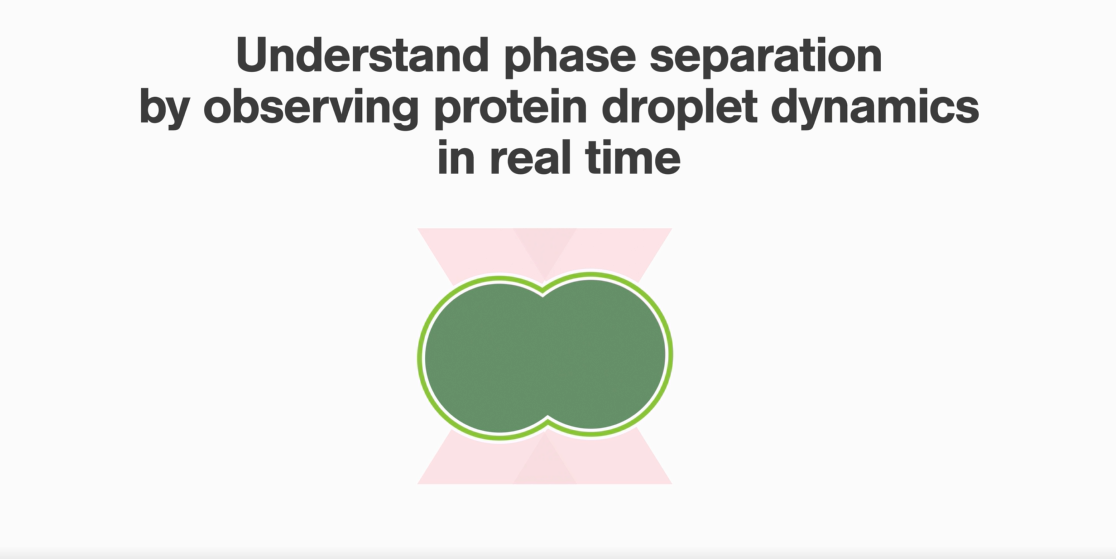

Variations in low-complexity domains and how they influence protein droplet solidification

Many peptides or proteins involved in phase separation contain low-complexity domains that can induce protein and amyloid aggregates, involved in some neurodegenerative diseases. Here, researchers from the lab of Dr. Bo Sun at ShanghaiTech used the C-Trap to assess how variations in low-complexity domains influence droplet solidification.

Similar to the above-mentioned experiments, the investigators used force-induced droplet fusion to evaluate peptide droplet properties. They evaluated the influence of low-complexity domain cores within hnRNPA1 proteins called reversible amyloid core (RAC).

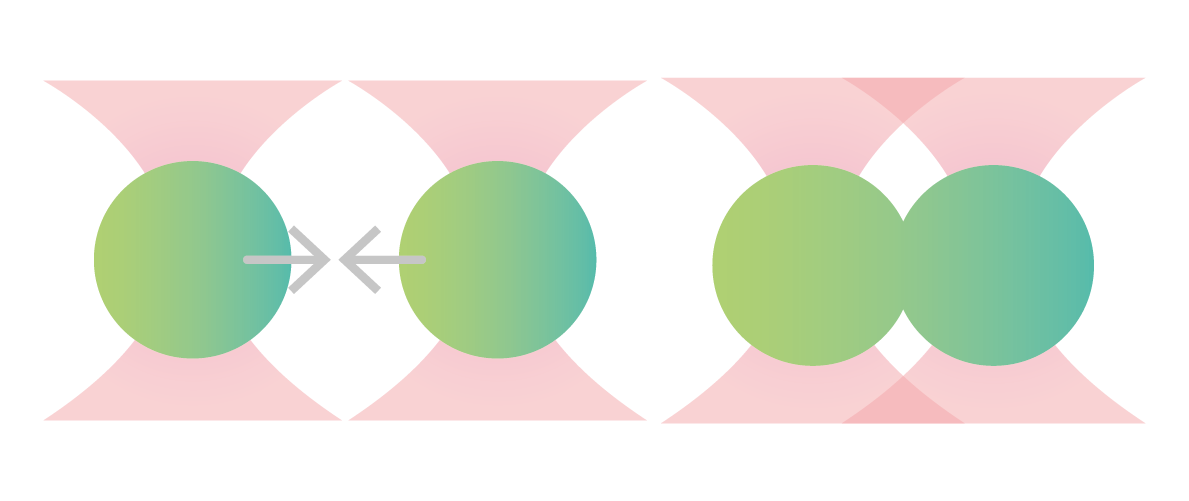

Compared with wild-type hnRNPA1 droplets, the deletion of hnRAC1, a specific segment within the protein, resulted in faster droplet fusion (10 seconds and 8 seconds, respectively). Conversely, hnRAC1 missense mutation of the aspartic acid to valine (D214V; associated with irreversible amyloid formation) resulted in an even slower droplet fusion (16 seconds; Figure 1).

Application note | Phase separation

1 Time-lapse images comparing the times to relaxation of protein droplets consisting of wild type (WT), RAC-depleted (ΔhnRAC1), or RAC-mutated (D214V) during optical tweezer-induced droplet fusion. Highlighted images indicate the time point of droplet fusion. Image source: Gui et al, Nature Communications, 2019 (CC BY).

The effect of molecular crowders on droplet fusion

The cellular environment contains macromolecules that can change the molecular and structural properties of the cell in a concentration-dependent manner. To understand how molecular crowding affects phase behaviors, researchers tested the fusion properties of protein droplets at different concentrations of model molecular crowder.

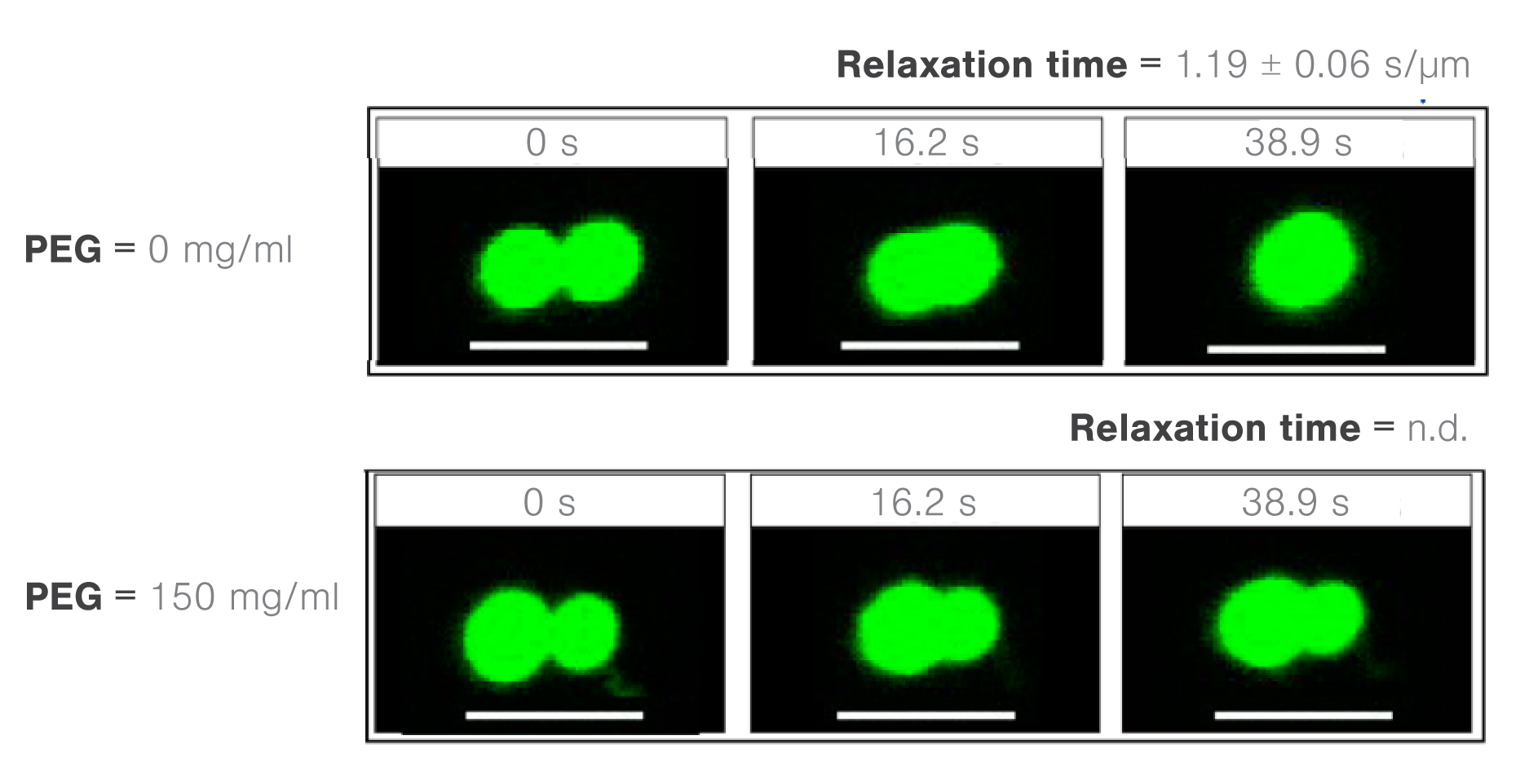

Using the polyethylene glycol PEG8000 as a model structure, the researchers measured the concentration-dependent effect of molecular crowders on the properties of FUS protein droplets.

They moved one of two trapped FUS droplets towards the other at a constant velocity and timed their fusion (time-to-relaxation) at different PEG8000 concentrations.

While the absence of PEG8000 crowders resulted in a fast droplet fusion (about 200 ms/μm), the presence of 150 mg/ml PEG8000 almost arrested the condensation (Figure 2).

Application note | Phase Separation

The effect of RNA/RNP interactions on the fusion of protein droplets.

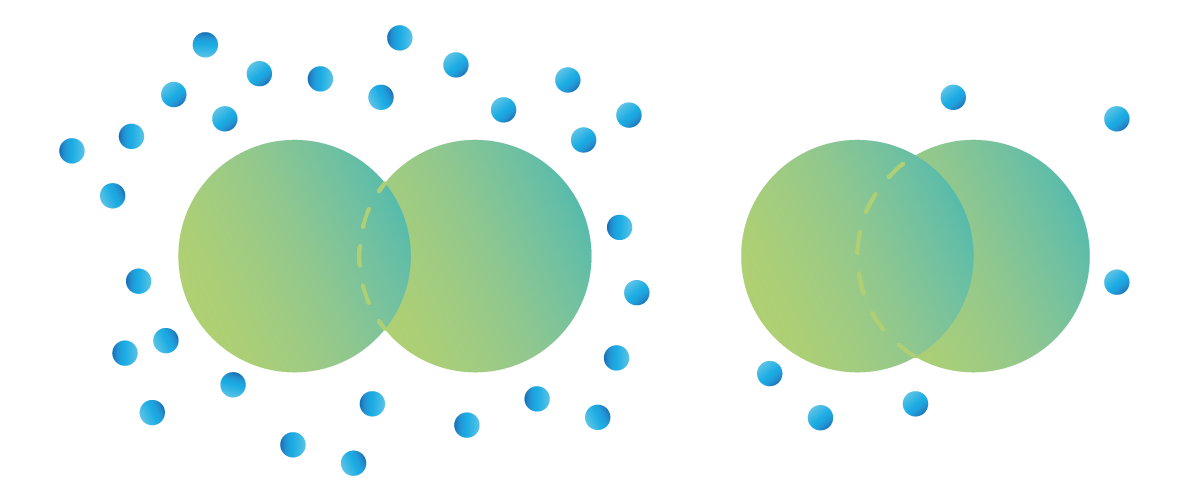

Previous in vitro experiments have shown that high RNA-to-ribonucleoproteins (RNA-to-RNP) ratios can inhibit the condensation between protein droplets. By contrast, low RNA-to-RNP ratios can promote the same process. Consequently, scientists from the Banerjee lab at the University at Buffalo investigated the condensation properties between different RNAs and polypeptides.

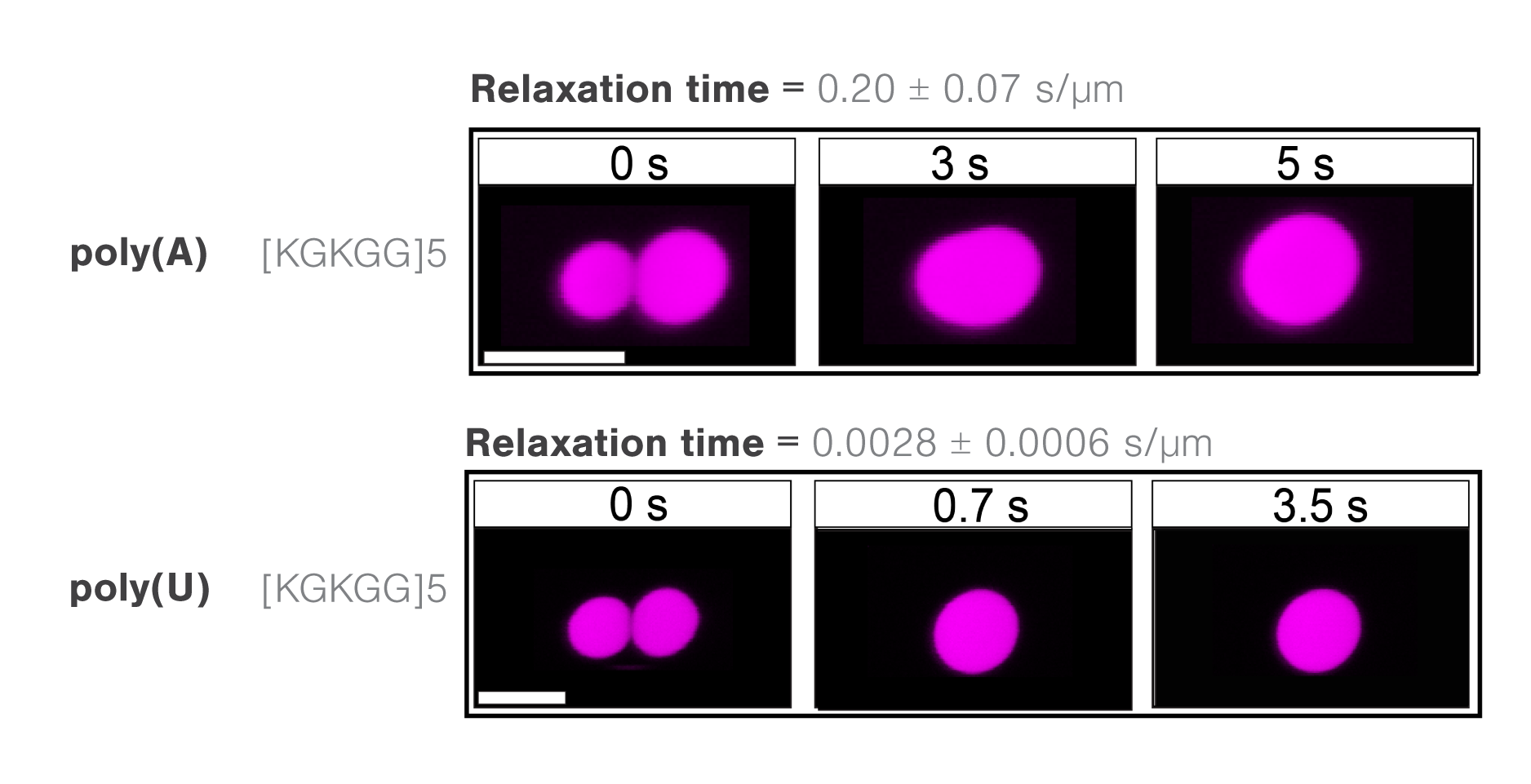

The researchers assessed the molecule-dependent effect of interactions between poly(A) or poly(U) RNAs and different peptide domains (R/G-rich or K/G-rich) on droplet stability, measure through droplet fusion.

They found that peptide droplets composed of K/G-rich peptides and poly(U) fused twice as fast (mean, 0.0028 s/µm) as droplets with R/G-rich peptides and poly(A) RNA (Figure 3). The results indicate a higher fluidity and lower viscosity in the former structure and suggest that short-range attractions and long-range forces regulate RNA–peptide condensate formation.

Application note | Phase separation

Microrheology, viscosity, and elasticity of protein droplets upon increasing salt concentrations

The degree to which biomolecules interact in droplet structures ultimately affects the resulting viscosity and elasticity, subsequently affecting their functions, for example, diffusion or structural rigidity. The C-Trap can measure the rheology of protein droplets as a function of different conditions, including salt concentrations.

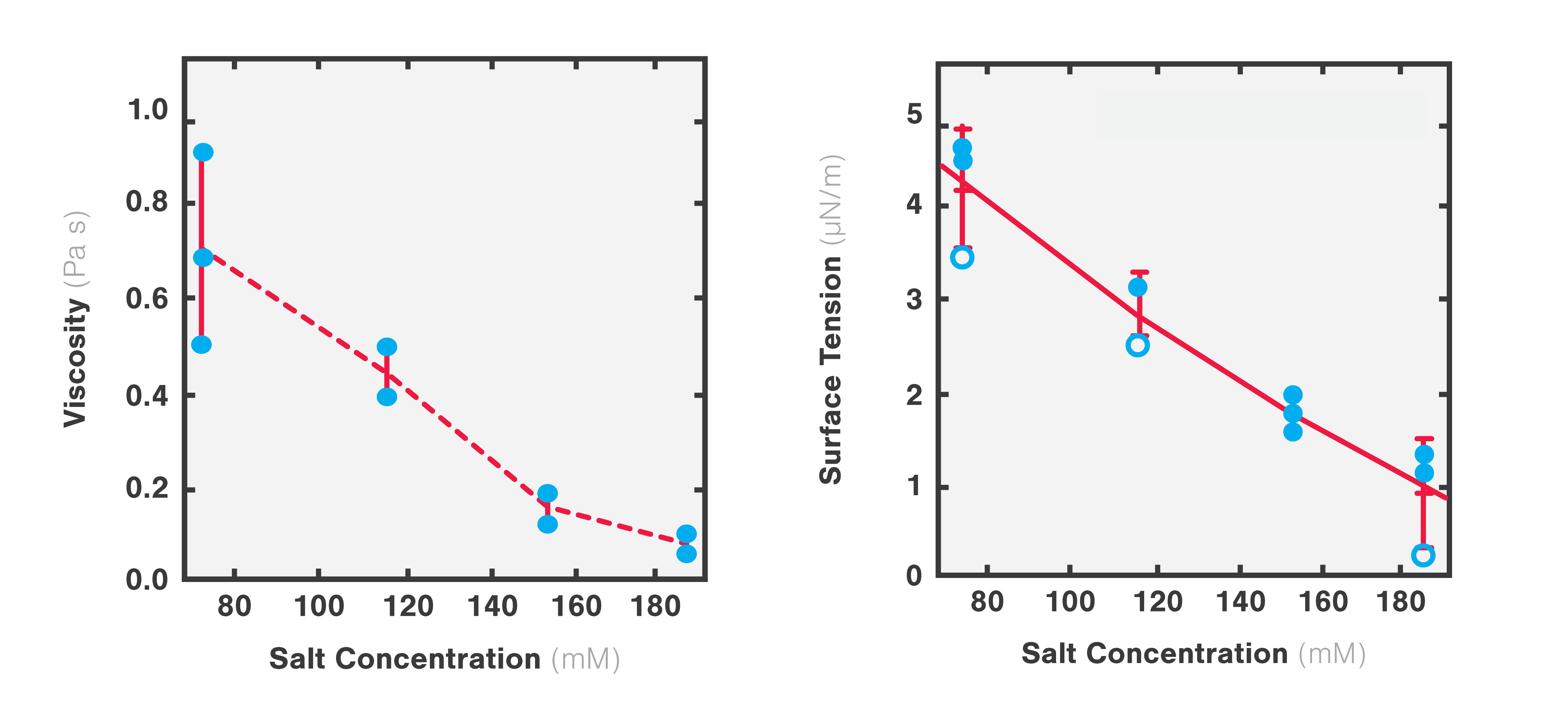

Using two optical traps, scientists from the Hyman lab at the Max Planck Institute of Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics could study the microrheology of protein droplets consisting of PGL-3 proteins in different salt concentrations (75, 115, 150, and 180 mM KCl).

They brought two independently trapped beads into adhesive contact with the droplet and applied force on one bead, moving it bi-directionally to deform the droplet. Since the forces needed to move the trap changes with altered thickness, they could measure the structure’s viscosity as a result of different salt concentrations.

The team found that both the viscosity and surface tension of the protein droplet decreased with increasing salt concentrations (1 to 0.1 Pa s and 5 to 1 µN/m, respectively: Figure 4).

Application note | Phase separation